Documentation sites

Last updated on 2026-03-10 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do I present comprehensive information to users of my research software?

- How do I generate a website containing a user guide to my code?

- What should a good documentation website contain?

- How do I publish my software documentation on the internet?

Objectives

- Learn about documentation websites for software packages.

- Gain basic familiarity with some common website generation tools.

- Understand the basics of structuring a documentation website.

- Be able to set up a static site deployment workflow.

Documentation websites

A documentation website is a user guide and reference manual for a library of research code. Up to now, we’ve looked at ways to put helpful notes in our code, but now we’ll learn how to write a longer, more complete guide to the research tools you create.

A documentation site brings all your user guidance into one place. This kind of resource may be prepared for research software and will usually contain an introduction, installation instructions, a user guide, troubleshooting tips, and an in-depth reference section.

To get an idea of this, here are some links documentation websites for widely-used data analysis and research software packages:

- pandas is a data processing library for the Python programming language.

- ggplot2 is a plotting package for the R statistical language.

- scikit-learn is a machine learning library for the Python programming language.

Evaluate these documentation sites.

- What do you like about them?

- How approachable are they as a new user?

- What do you find difficult to understand in this material?

Keep these impressions in mind as we explore what makes a good documentation site and how to build one.

Why create a website?

There are many advantages to building a documentation site to provide a information-rich resource for researchers who use your code at institutions all around the world.

Advantages

These sites can work as hubs for collaboration, sharing the latest updates, and encouraging people to take up your system and get involved in improving it. The effort of setting one up will be rewarded in the long run because you will have created a valuable asset that will foster collaboration and knowledge sharing in your research community.

A key foundation stone of modern digital research practices is the ability to replicate results by reproducing analytic workflows. Clear, thorough documentation of the research code ensures that researchers can repeat processes and verify results and other people’s outputs.

Documentation sites are really useful for introducing new users to your software. It makes it much easier and faster for new users to get started using your software to boost their research. It’s one of the most effective ways to create a user base that has a sophisticated understanding of the research code, which is essential for them to adapt it to the complex problems that often arise in research contexts.

They’re also a valuable resource for your existing user base, enabling them to look up reference material or search the manual to find new capabilities they weren’t aware of before. This will increase the potential for your software to increase the productivity of other research teams.

When to use one

Although the advantages are numerous, not all software packages require a comprehensive documentation website. However, for any code project that is growing in the number of collaborators, users, and technical complexity, consider coordinating the team to write one as soon as possible to help the project continue its healthy growth.

When is it appropriate to establish a documentation website? Consider the following factors:

- How many resources will it take to write and maintain?

- How many end-users need the information?

- Is there a simpler format that can convey the same information?

Once you’ve decided to create a documentation site, the next step is to decide what to put in it and how to write it.

Writing style

As we discussed in the episode on READMEs, it’s important to strive to use everyday, jargon-free language. It helps to set an approachable tone that encourages others to use the software and get involved with the project. This will ensure that the code is accessible to the widest possible layers of the research community and foster collaboration.

Always consider the target audience of your documentation, because your user base may be unaware of some of the unstated assumptions and technical background knowledge that you take for granted.

Contents

Documentation pages contain comprehensive information about a particular piece of research software. Think of it like a user manual for your car or an instruction guide for building a piece of furniture.

Research context

For research software, it may be important to explain the theoretical background or statistical methods that are used and explain the domain-specific assumptions that were made when the code was designed and written. It’s good practice to provide a concise summary of the relevant concepts and link to external sources such as papers, books, and other websites for users to take a deeper dive into the principles and algorithms used.

Installation instructions

This section provides a detailed walkthrough of the steps required to install the package onto their computer, with details that are specific to their operating system.

Tutorials

It can be very useful to include an in-depth “Getting Started” guide that provides step-by-step instructions to introduce a new user to your software package. It might guide the user through each aspect of the tool’s functionality and features so they’re able to become familiar with it in a more approachable way.

A series of code examples to demonstrate how to use the software in different contexts can be very useful for users to get off the ground in implementing common research workflows to achieve their specific goals.

User reference

If you have written functions that are intended to be use in other researchers’ code, then an in-depth explanation of these procedures is essential reference material. In the world of software engineering, these detailed appendices are called API references, which list each function and describe how the arguments may be used to control how the code works. This content may be automatically generated from the documentation strings.

Troubleshooting

As issues come up with your research code, and are eventually resolved and clarified, make a note of the causes of these troubles and make them available to the entire user base in your documentation site. This will help users to identify and fix common misunderstandings and technical problems they may run into when utilising your code.

This prevents a situation where potential solutions to common issues do exist, but are scattered around the internet and are the exclusive knowledge of a few individuals and are hard to find.

Tools

There are various tools available to build documentation sites for your research software. The right choice depends on your programming language, the complexity of your project, and how much control you need over the site’s appearance.

GitHub Wiki

If you are publishing your code on GitHub, which is a web service that hosts code repositories, then one of the easiest ways to create a documentation site is to use the wiki feature on that platform. This is a great way to write detailed, structured documents containing long-form content that describes aspects of your software. What’s more, it’s available alongside your code so your documentation and software are located in one place.

As with readme files, the text that appears on GitHub is formatted using Markdown syntax.

Getting started

To create a wiki, which is a simple, easy-to-edit web site, go to the main page of your code repository on GitHub and click on the Wiki button on the top menu. For a detailed walkthrough of this process, please read adding or editing wiki pages on the GitHub documentation.

GitHub Wikis

For more information about the wiki feature on GitHub, see Documenting your project with wikis on the GitHub documentation.

Create a wiki page

Navigate to your code repository on GitHub and create a wiki. Add a page that describes how to install your software.

Consider what information a new user would need to get started. How does it feel to write for that audience?

Standalone site generators

For projects that need more structure, customisation, or automatic generation of content from code, standalone site generator tools are a good choice.

Documentation sites for R packages

It’s also possible to generate a documentation site to accompany R packages that you create. For more information about this, please refer to the book R Packages by Hadley Wickham, which has a chapter on documentation websites.

Sphinx

Sphinx is a tool for building documentation websites that is commonly used amongst developers of Python packages, although it’s also compatible with other programming languages. It doesn’t currently support packages written using the R statistical language.

Sphinx is a documentation generator tool that takes plain text files that use a markup syntax (such as reStructuredText or Markdown) for formatting the content of your documentation site and transforms them into various output formats, ready to be published on the internet. It has a number of useful features, but in this module we’ll learn the basics to document our research code.

Getting started

Let’s use Sphinx to create a documentation site for our Python code.

Installing Sphinx

Navigate to the root folder of your code project. Create a virtual

environment using venv which is a

separate area in which to install the Sphinx package. This command will

create a virtual environment in a directory called

.venv/

This will create a subdirectory that contains the packages we’ll need to complete the exercises in this section.

Run the activation script to enable the virtual environment. The specific command needed to activate the virtual environment depends on the operating system you are using.

Use the Python package manager pip to install Sphinx.

Start a new Sphinx project

Sphinx includes a command to set up a new project called sphinx-quickstart. Navigate to your project’s root folder and run the following command.

This will initialise the configuration files for a new Sphinx site in

a subdirectory called docs/ and prompt you to enter the

following options:

- Project name: Birdsong Identifier

- Author name(s): Bill Oddie

- Project release []: 1.0

Sphinx options

To find out more about the Sphinx configuration files, please read their guide to defining document structure on the Sphinx documentation.

Building the site

In this context, building means taking our collection of Sphinx files and converting them into the source code files that define a website. Sphinx will create HyperText Markup Language (HTML) files, which is the markup language for pages that display in a web browser commonly used on the internet.

To build our site, we run the sphinx-build

command using the -M option to select

HTML syntax as the output

format.

Sphinx will load our files from the docs/ directory and

output the built HTML files in the docs/_build

directory.

The file docs/_build/html/index.html contains the home

page of your new documentation site! Open that file to view your

handiwork.

Autodoc

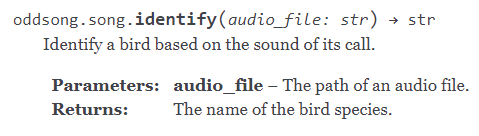

It can be useful to automatically populate our documentation sites by converting our documentation strings into formatted text. We can achieve this using the autodoc plugin for Sphinx.

Configuring Autodoc

Let’s set up the options for autodoc. (If you struggle

with these steps, please refer to the template

project.)

Add the following lines to docs/conf.py which

PYTHON

# Our Python code may be imported from the parent directory

import os

import sys

sys.path.insert(0, os.path.abspath('..'))This ensures that Sphinx can access our Python code by pointing at

the root directory of our project. The .. syntax means “one

folder up”, which means autodoc will search in the root

directory for code to import.

The Python code uses sys.path,

a list of locations to search for code. By modifying the Python

module search path, we allow autodoc to locate and

import our code modules from a specific directory that is not in the

default search path.

This is often necessary when working with project structures that involve multiple directories, helping the interpreter to find code that isn’t installed in the standard library location.

Next, edit docs/index.rst and add the following lines to

instruct Sphinx to automatically generation documentation for our Python

module.

This reStructuredText (reST) markup language has the following elements:

-

..indicates a directive within a reST document that is used to configure Sphinx. -

automodule::indicates a specific directive to useautodocto automatically generate documentation for a module. -

oddsong.songis the path to our Python module, for which documentation will be created. -

:members:is an optional argument for the automodule directive that instructs Sphinx to include documentation for all members (functions, classes, variables) defined within the specified module.

For more information about reST, please read the Introduction to reStructuredText by Write The Docs.

Now, when we build our site, Sphinx will scan the contents of the

oddsong Python module and automatically generate a useful

reference guide to our functions.

The result looks something like this:

Automatically generate content

Try using autodoc to analyise your own code and build a

documentation site by following the steps above.

After the sphinx-build command has completed

successfully, browse the contents of the docs/_build/html

folder and discuss what you find.

Publishing

Now that you’ve started writing your documentation website, there are various ways to upload it to the internet so that others can read it.

GitHub Pages is a free hosting service built into GitHub. It can automatically build and publish your site whenever you push changes to your repository, making it a convenient choice if your code is already hosted on GitHub.

Read the Docs is a dedicated documentation hosting platform that integrates with Sphinx and other generators. It automatically rebuilds your documentation when you push new commits and provides versioned documentation so users can browse the docs for older releases of your software.

Choosing a hosting platform

Both platforms offer free tiers for open-source projects. GitHub Pages is simpler to set up, while Read the Docs provides more documentation-specific features such as version switching and search.

The detailed steps for configuring deployment to these platforms are beyond the scope of this course, but both provide clear guides to get you started.

- Structured documentation websites are very useful for users to learn to use all kinds of digital systems, ensuring its successful adoption by the wider research community.

- Documentation sites contain comprehensive installation instructions, user guides, and troubleshooting tips.

- There are several libraries that may be used to generate documentation sites.

- Documentation websites may be deployed to a hosting platform.

Further resources

Please review the following material which provides more information about some of the topics covered in this episode.

- Sphinx Getting Started

- Write the Docs Introduction to reStructuredText

- GitHub documentation About wikis

- Write the Docs Tools for documentation writing