Limitations

Last updated on 2026-01-14 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 10 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What are the limitations of

venv? - What are the limitations of virtual environments more generally?

Objectives

- Understand the limitations of using

venvand some alternatives - Understand the inherent limitations of virtual environments, and potential solutions for them

Specific limitations of venv

While venv is a relatively simple option for setting up

and managing your virtual environments it does have some key

limitations:

- Python version management

- Automatically keeping track of installed packages

1. Python version management

There are differences between the different versions of Python. With the most extreme example being the incompatibility between Python 2 and Python 3. Depending on the complexity of your code, changes between version may not affect you, but it can be hard to tell without trying a newer version. If you want to make your code truly reproducible you should include some information about which version of Python you used to produce your results.

venv uses whichever version(s) of Python you have

installed on your machine, but neither venv or

pip records information about which version of Python you

are using.

It is, of course, possible to include this information with the instructions on how to run your code, but as highlighted multiple times it is better to have an automated solution.

2. Automatically keeping track of installed packages

As shown, using venv with pip can create a

list of dependencies for your project, but this has to be created

manually and updated manually whenever you modify the dependencies for

your project.

Ideally this would be updated automatically as packages are added and removed, so as to avoid any mistakes or forgetting to update it after changes have been made.

Solutions

There are quite a few different tools that have been developed to

deal with these issues. Out of these the ones available, I have found

most useful to be uv and conda/ miniforge/

pixi.

These tools combine package, environment, and Python version

management, allowing you to do everything that pip and

venv do, while also being able to easily switch between

different Python versions. Both will also record the version of Python

used within an environment allowing you to capture both the ‘package’

and ‘language’ layers of your computational environment in one go.

There are some differences between them though:

uv:

- Built as a replacement for pip and

venv

- Uses the same package repositories as pip

- Uses the same virtual environment structure as venv

- Auto updating of environment dependencies file (equivalent to

requirements.txt)

- Noticeably faster for installing packages than pip or

conda

- Not reached a version 1 release (yet!)

conda/miniforge/pixi:

- Provide pre-compiled binaries for packages, which means faster

installation

- Includes other languages (notably R)

- They use their own package repositories, so may not be inter-operable

with other Python tools without a bit of fiddling

- They use their own virtual environment structure that is different

from the one explained here

For a broader discussion of the tooling available for Python version/package/environment management have a look at these two blog posts:

Python Environment Jungle: Finding My Perfect Workflow

An unbiased evaluation of environment management and packaging tools

James Thomas has tutorials

for both uv and pixi

Prior to 2025 I primarily used either pip and

venv or conda to manage my Python

environments. However, for all new Python projects since the start of

2025 I have used uv and will continue to do so wherever

possible. I haven’t used pixi at all.

Once you feel comfortable with the concepts discussed in this

material I would suggest giving uv a try, although

ultimately the best tool for this is the one that suits your workflow

best.

General limitations of virtual environments

Beyond the specific limitations of venv, virtual

environments in general have one key limitation:

- They are not able to control the underlying system they are working within.

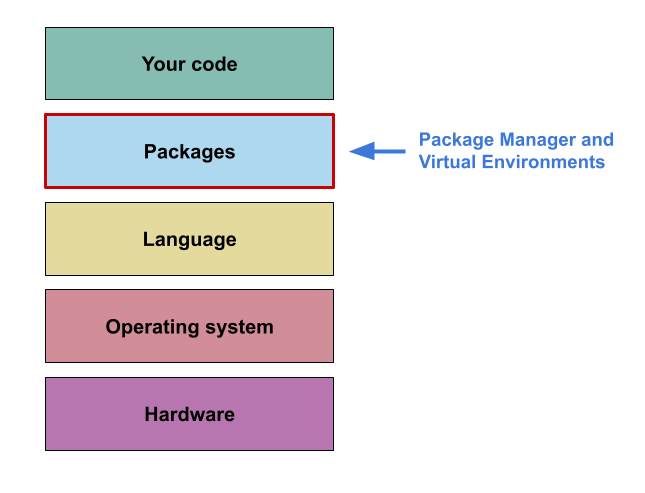

If we go back to our diagram showing the different layers of your computational environment, you can see that virtual environments only address the layer of the environment immediately below your code.

If you are using something like conda,

miniforge or uv, then you may be able to

extend that to the ‘language’ layer. But these tools are not able to

capture the ‘operating system’ layer.

Depending on the degree of computational reproducibility you are looking for, capturing the ‘package’ and ‘language’ layers may be enough. However, if you are looking for byte-for-byte reproducibility you will likely also want to capture as much of the computational environment as possible, and so you will need to turn to other tools.

Capturing the operating system layer

There are multiple different tools that can be used to capture the layer below ‘package’/ ‘language’

Virtual machines

This is one of the more commonly known tools for capturing and

replicating the ‘Operating System’ layer a computational environment.

Virtual machines (VMs) are effectively an emulation or virtualisation of

an operating within your own “host” operating system. For example, using

a virtual machine I can create and run a Windows XP operating system

within my Windows 10 machine. These can also be interacted with using

familiar point and click interfaces, and can be customised to access a

specific portion of the host machines CPU, memory, disk, etc.

It is possible to take a snapshot of an exiting VM for distribution, or

use an ‘Infrastructure

as code’ tool such as Ansible to

write a script to (re)create a specific environment (e.g. install

specific software, etc)

Containers

Containers are similar to Virtual machines in that they virtualise an

operating system, but containers are typically more lightweight than VMs

as they only contain software and files that are explicitly defined in

order to run the project contained within them.

They also typically don’t have a GUI in the same way the OS on your

computer does (although some containers will provide an interface,

e.g. RStudio Server).

If you want to create an environment on your machine and then run it on

something more powerful (like a HPC) then containers are a good way of

achieving this, although this can become complex due to limited

permissions and/or underlying hardware.

Andy Turner of the EPCC has an excellent course providing an introduction to using containers for reproducible computational environments.

Nix/Guix

Nix(OS) and Guix also provide a way of capturing the

computational environment below the ‘packages’ and ‘language’ layers,

but take a slightly different approach to this than VMs and

Containers.

These are package managers based on the idea declarative configurations,

that is: “specify your setup with a programmable configuration file, and

then let the package manager arrange for the software available on the

system to reflect that”.

This is similar to what pip is doing with the

requirements.txt file described previously, but for an

entire Operating system. However, this approach takes it one step

further by allowing multiple versions of the same package to exist on a

machine simultaneously.

For a more complete outline of this approach see this post

-

pipandvenvprovide the most basic functionality for capturing this level of your computational environment. - Other tools (e.g.

uv,pixi) are available that build on this basic functionality that would be worth investigating and incorporating. - Virtual environments can only capture a portion of the computational environment.

- Projects that require more of the computational environment to be captured may need more advanced tools (e.g. VMs, containers, Nix/Guix) to achieve this.