Principles of Code design

Last updated on 2024-12-04 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How to write maintainable, readable, resusable and scalable code?

Objectives

- Be familiar with standard principles of code design

- Understand what they mean and how to apply them

Coding principles are guidelines and best practices that anybody writing code should follow to write clean, maintainable and efficient code. They enhance code quality and ensure it is readable, reusable and less prone to errors.

You aren’t gonna need it (YAGNI)

Introduction

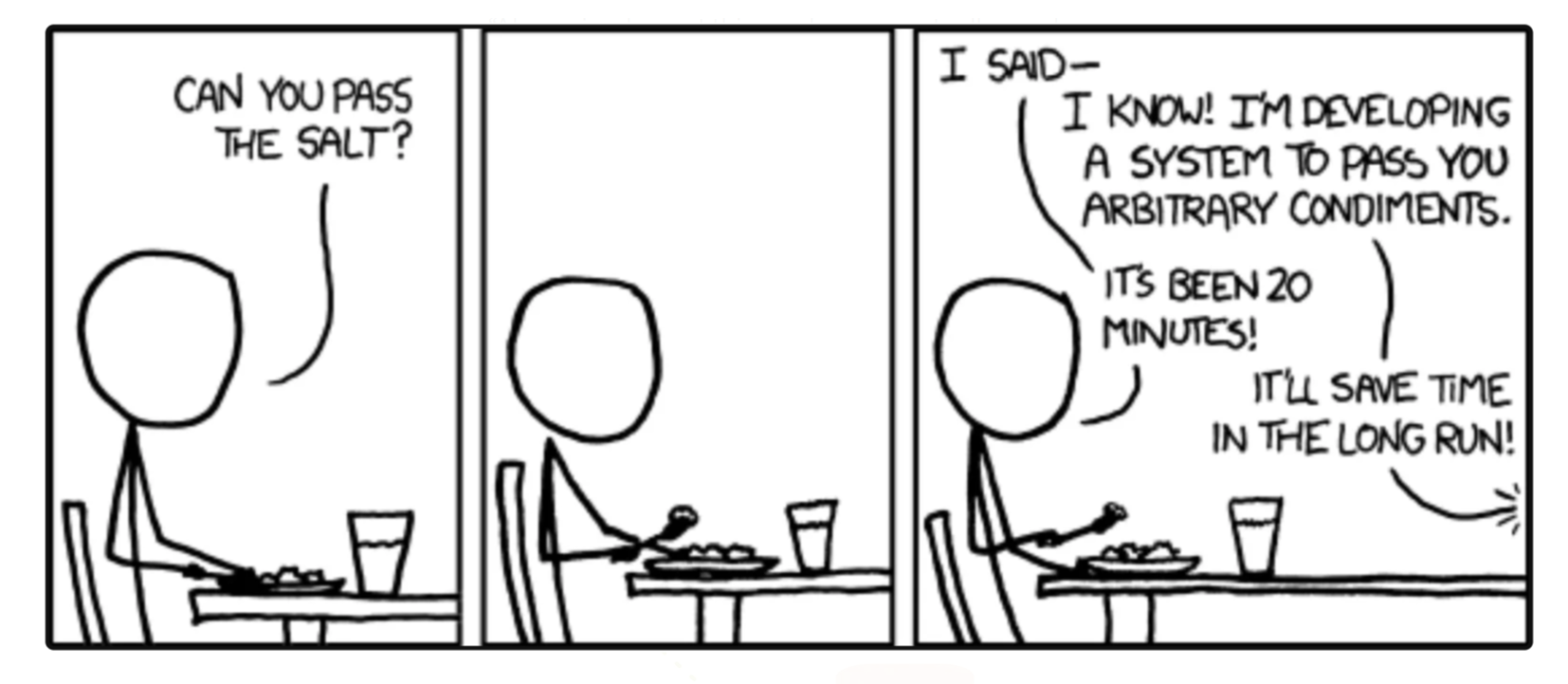

The principle YAGNI stands for “You Aren’t Gonna Need It”. This principle encourages you to build only what is needed right now, avoiding adding features for hypothetical future needs. It comes from Agile programming and aims to reduce spending time and resources on unnecessary code and keep the code clean and understandable.

Why YAGNI is important:

- Simplicity: By avoiding unnecessary code you will reduce complexity, making it easier to read, maintain, and debug code.

- Saving Time: Don’t wast time by building features that may never be used.

- Flexibility: Writing only what is needed makes any changes in requirements easier to implement.

Applying YAGNI

Let’s consider the following instruction: create a function that implements a percentage discount price. Here is a solution that does not respect the YAGNI principle:

PYTHON

def calculate_discount(price, discount_type="percentage", value=10.0):

'''

This function applies a discount to a price

Parameters

----------

price : float

Original price

discount_type: str

type of discount [percentage of fixed]

value: float

discount to be applied

Return

------

discounted_price: float

final price after applying discount

Raises

------

ValueError

if the discount type is not 'percentage' or 'fixed'

'''

if discount_type == "percentage":

return price - (price * (value / 100))

elif discount_type == "fixed":

return price - value

else:

raise ValueError("Invalid discount type")In that example, the software engineer has planned for possible other use cases (different type of discount) while not being required. It is an example of over-engineering. A better implementation would be:

PYTHON

def calculate_discount(price, discount_percentage):

'''

Function that applies a discount. The discount is given as a percentage of the original price.

Parameter

---------

price: float

original price

Return

------

final_price: float

final price after applying discount

'''

final_price = price - (price * (discount_percentage / 100))

return final_priceExercise

Challenge

Context: You’re working on a feature to calculate the final price of

items in a shopping cart. Right now, the only two requirement are (1) to

apply a fixed 10% discount to the total cart price and (2) return the

final price with a $ sign in front of the total price

(e.g. $42.2). However, the initial implementation includes additional

features that anticipate potential, but not confirmed, future

requirements.

PYTHON

def calculate_final_price(prices, currency="USD", discount_type="percentage", discount_value=0.1, include_shipping=False, shipping_cost=5.0):

# Calculate the initial total price

total = sum(prices)

# Apply discount based on type

if discount_type == "percentage":

total -= total * discount_value

elif discount_type == "fixed":

total -= discount_value

# Include shipping if specified

if include_shipping:

total += shipping_cost

# Format total with currency symbol

if currency == "USD":

return f"${total:.2f}"

elif currency == "EUR":

return f"€{total:.2f}"

else:

raise ValueError("Unsupported currency")Work on the calculate_final_price function to apply the

YAGNI principle by removing unnecessary parameters and logic, focusing

only on the known requirements.

Keep it simple, Stupid (KISS) & Curly’s Law

Introduction

The KISS Principle stands for “Keep It Simple, Stupid” and points out that writing simple code should be a primary goal in design. Complex structure often leads to unreadable and error-prone code. This is especially important in research where maintaining code over a long time period is essential.

Why KISS is important?

- Readability: Simple code is easier to understand. There is a high chance that the person who will read your code the most is yourself, so help your future self.

- Maintainability: Bug are easier to be found and fixed when each component is simple.

- Upgrade: A simple code is easier to adapt to changes in the requirements.

It is easy to recognize complex code. When you have too many nested

loops or if statements it means that your code is not

optimal. In such case you might take a step back and try to simplify the

structure.

The Curly’s Law says that a function should focus on a single task. Each function should “do one thing” and “do it well,” meaning that if a function has multiple tasks, consider breaking it down.

Why is the Curly’s Law important?

- Reusability: Simple single-task function are easier to reuse.

- Bug fix: When you code is composed of simple function, potential issues are easier to localise.

- Testing: Simple single-task function are easier to test.

- Modularity: Code becomes more modular and organized.

Applying KISS and Curly’s Law : Simplifying a Complex Function

Let’s consider a function that compute the area of circles, rectangles and triangles:

PYTHON

def calculate_area(shape, dimensions):

'''

This function compute the area of a given geometrical shape

Parameters

----------

shape : str

shape to consider. Can be rectangle, circle or triangle

dimensions: list

of dimension to consider. For rectangle and triangle you need to give a list

of 2 numbers. For circle, you need to pass a list of one quantity (radius).

Return

------

area : float

area of the shape

Raises

------

ValueError

if the shape is not recognised

'''

if shape == "rectangle":

area = dimensions[0] * dimensions[1]

elif shape == "circle":

area = 3.14159 * (dimensions[0] ** 2)

elif shape == "triangle":

area = 0.5 * dimensions[0] * dimensions[1]

else:

raise ValueError("Unsupported shape!")

return area

area = calculate_area("rectangle", [10, 20])This function is able to compute the area of each shape. To apply KISS and the Curly’s law what you can do is to split this function into three simple independent functions:

PYTHON

def rectangle_area(length, width):

return length * width

def circle_area(radius):

return 3.14159 * radius ** 2

def triangle_area(base, height):

return 0.5 * base * height

# Simple and clear usage

area = rectangle_area(10, 20)In that version, functions are specific and easy to understand and there is no unnecessary complexity in shape management. It is easier to maintain and extend.

Exercice

Challenge

Let’s consider a function that processes data by removing values, calculating the average and returning a formatted result :

PYTHON

def process_data(data):

cleaned_data = [x for x in data if x is not None] # Remove missing values

average = sum(cleaned_data) / len(cleaned_data) # Calculate average

return f"Average: {average:.2f}" Using KISS and Curly’s law, rewrite this code.

PYTHON

def remove_missing(data):

'''

This function is removing missing data from a list

Parameter

---------

data : list

list of numbers

Return

------

cleaned_data: list

of data without missing values

'''

clenaed_data = [x for x in data if x is not None]

return cleaned_data

def calculate_average(data):

'''

This function computes the average of the input data

Parameters

----------

data : list

of numbers

Return

------

average : float

average of the data

'''

average = sum(data) / len(data)

return average

def format_average(average):

'''

Format the number as given in parameter as string.

Parameter

---------

average : float

number to format

Return

------

formatted_string : str

of the form 'Average: X.YZ'

'''

return f"Average: {average:.2f}"Don’t repeat yourself (DRY) - Rule of three

Introduction

The DRY Principle states: “Don’t Repeat Yourself.” It encourages you to minimize duplication by refactoring similar code patterns. This leads to more readable, maintainable, and scalable code.

Why DRY is it important:

- Improves Readability: Code is clearer when it’s not cluttered with repeated logic.

- Reduces Bugs: If you need to make changes, you only do it in one place, reducing the chance of errors.

- Saves Time: Updating and testing code is faster when code is organized with minimal duplication.

Using functions to avoid repeting code

Instead of writing the same code in multiple places in your script, create a function. This makes updates easier and avoids errors. For example consider the following code:

The same operation is repeated three times with a different value. If you create a function that makes this operation you can refactor your code:

Using loops instead of manual repetition

In the previous examples we still call the function three time which is not optimal. In general, If you’re applying the same operation to multiple elements, use a loop to avoid repeated code blocks:

Using constants for common values

When a value is repeated in multiple places, declare it as a constant variable. This way, you only need to change it once if necessary. Consider the following code:

The value 0.1 is repeated three times. If you want to

change it, you will need to do it three times. To save time and to add

some clarity to your code, you may want to declare the value

0.1, as follows:

Now if you want to change 0.1 to 0.2 you

need to do it only once. In addition, now you have a better idea of what

that constant is! The code is already clearer.

Challenge

Write a code, without repetition, that produces the following output:

Hello, Alice!

Hello, Bob!

Hello, Charlie!Summary

DRY helps you write clear, efficient, and error-resistant code. Use functions, loops, and constants to reduce repetition. A DRY approach saves time and effort in the long run, especially when scaling or debugging code.

It is important to note that prematurely refactoring a code might lead to the unnecessary complexity. This is why DRY is often associated to the Rule of Three. The latter is a guideline suggesting that you should wait until a piece of code is repeated three times before refactoring it. It ensures that you only refactor when a pattern is stable and repeated enough time.

Principle of least astonishment (POLA)

Introduction

The Principle of Least Astonishment (POLA) states that code should work in a way that does not surprise its users and maintainers. POLA encourages you to design code that aligns with common expectations.

Why POLA is important:

- Usability: When code works as expected, users and maintainers are less likely to misuse or misunderstand it.

- Maintainability: Familiar and predictable patterns make the code easier to maintain and upgrade.

- Collaboration: Using consistent and intuitive code make it easier for multiple people to work with and develop.

Common violations

Here are three common violation of POLA:

Naming Conventions: Function or variable names that don’t align with their purpose often lead to problems

Unexpected Return Types: Functions that return types users wouldn’t expect, such as a function sometimes returning an integer and other times returning None.

Multiple Functionalities: Using functions for multiple unrelated tasks often leads to unexpected behaviors.

Applying POLA

Example 1: Consider a function that returns different types based on a condition, which could confuse users who expect one type.

PYTHON

def calculate_total(items):

if not items:

return None # If no items, return None

return sum(items)The problem in that function is that depending on a condition, the returned value has a different type. To overcome this problem a potential solution is to return a number anyway:

PYTHON

def calculate_total(items):

if not items:

return 0 # Return 0 instead of None for consistency

return sum(items)With this solution, the user of the code will always get the same type out of that function.

Example 2: Consider a function that does two different tasks: processing some data and save them in a file.

PYTHON

def process_data(data, save=False):

cleaned_data = [d.strip() for d in data]

if save:

with open('data.txt', 'w') as f:

f.write('\n'.join(cleaned_data))

return cleaned_dataThe user may not expect that processing data will save them into a file as well. This can lead to data being overwriten. To overcome this potential problem, you might want to separate the two functionalities into two different functions:

PYTHON

def process_data(data):

return [d.strip() for d in data]

def save_data(data, filename='data.txt'):

with open(filename, 'w') as f:

f.write('\n'.join(data))This solution keeps each function’s purpose clear.

Exercice

Challenge

Refactor calculate area to make it more predictable and

intuitive.

PYTHON

from math import pi

def calculate_area(shape, a, b=0):

if shape == "rectangle":

return a * b # Expects both `a` and `b`

elif shape == "circle":

return pi * (a ** 2) # Ignores `b`

elif shape == "triangle":

return 0.5 * a * b # Expects `a` as base and `b` as height

else:

return "Unknown shape"

# Example usage:

print(calculate_area("rectangle", 5))

print(calculate_area("circle", 3, 4))

print(calculate_area("triangle", 6, 3))

print(calculate_area("hexagon", 5, 5)) PYTHON

from math import pi

# Specific functions for each shape

def rectangle_area(length, width):

if length <= 0 or width <= 0:

return "Error: Length and width must be positive numbers."

return length * width

def circle_area(radius):

if radius <= 0:

return "Error: Radius must be a positive number."

return pi * radius ** 2

def triangle_area(base, height):

if base <= 0 or height <= 0:

return "Error: Base and height must be positive numbers."

return 0.5 * base * height

# Example usage

rect_area = rectangle_area(10, 5) # Expected: Valid rectangle area

circle_area_invalid = circle_area(-3) # Expected: Error message

tri_area = triangle_area(6, 3) # Expected: Valid triangle area

rect_invalid = rectangle_area(10, -5) # Expected: Error message

# Output results

print(f"Rectangle Area: {rect_area}")

print(f"Circle Area: {circle_area_invalid}")

print(f"Triangle Area: {tri_area}")

print(f"Invalid Rectangle Area: {rect_invalid}")