Versioning

Last updated on 2026-02-17 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- Why is versioning essential in software development? What problems can arise if versioning is not properly managed?

- How can automation tools, such as those for version bumping, improve the software development process?

- Why is it important to maintain consistency and transparency in software releases?

Objectives

- Explain why versioning is crucial for software development, particularly in maintaining reproducibility and ensuring consistent behaviour of the code after changes.

- Understand how to use

setuptools_scmfor automating version bumping in Python projects.

Introduction

In previous episodes, we developed a basic Python package to demonstrate the importance of software reproducibility. However, a crucial question that we haven’t addressed yet is: how can we, as the developers, ensure that a change in our package’s source code does not result in the code failing or behaving incorrectly? This is also an important consideration for when you are releasing your package.

One of the pitfalls of packaging is to fall into poor naming

conventions, even for scripts. For instance, how many times have you

worked on scripts that was named my_script_v1.py or

my_script_final_version.py? What were your main challenges

with this approach, and what alternative solutions can you think of to

circumvent this naive approach?

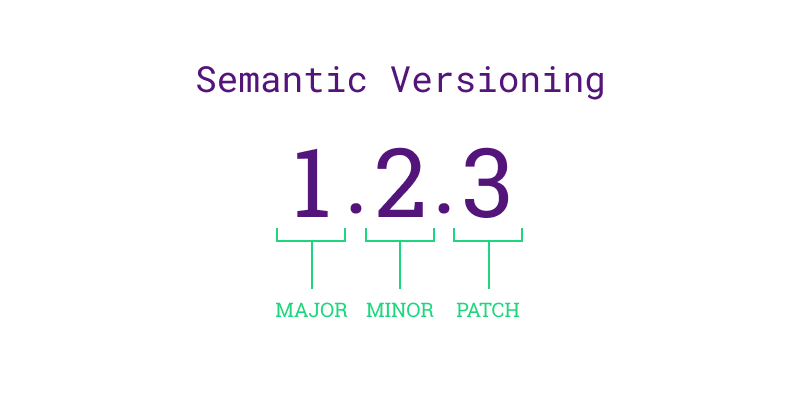

Semantic Versioning

The answer the question above is based on a concept called

versioning. Versioning is the practice of assigning unique

version numbers to different states or releases of a given package to

track its development, improvements, and bug fixes over time. The most

popular approach for Python packaging is to use the Semantic Versioning framework, and can be

summarised as follows:

Given a version number X.Y.Z, where X is the major version, Y is the minor version and Z is the patch version, you increment:

X when you make incompatible API changes,

Y when you add functionality in a backwards compatible manner,

Z when you make backwards compatible bug fixes.

Recall: API

An Application Programming Interface (API) is the name given to the way different programs or parts of a program to communicate with each other. It provides a set of functions, methods that can be used to interact with a piece of software or data services. Commonly, APIs are used within web-based applications to enable users to receive information from a given service, such as logging into social media accounts, creating weather widgets, or finding geographical locations.

The first version of any package typically starts at 0.1.0, and any

changes following the semantic versioning rules above results in an

increment to the appropriate version numbers. For example, updating a

software from version (0.1.0) to (1.0.0) is called a

major release. Version (1.0.0) is commonly

referred to as the first stable release of the package.

An important point to highlight is the semantic versioning guidance above is a general rule of thumb. Exactly when you decide to bump the versions of your package is dependent on you, as the developer, to be able to make that decision. Developers typically take the size of the project into account as a factor; for example, small packages may require a patch release for every individual bug that is fixed. On the other hand, larger packages often group multiple bug fixes into a single patch release to help with tractability because making a release for every fix would accumulate in a myriad of releases, which can be confusing for users and other developers. The table below shows 3 examples of major, minor and patch releases developers made for Python.

| Release Type | Version Change | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Major Release | 2.0.0 to 3.0.0 | Introduced significant and incompatible changes, such as the print function and new syntax. |

| Minor Release | 3.7.0 to 3.8.0 | Added new features like the walrus operator and positional-only parameters, backward-compatible. |

| Patch Release | 3.8.0 to 3.8.1 | Fixed bugs and made performance improvements without adding new features or breaking changes. |

Pre-release Versions

Pre-release versions in semantic versioning are versions of the software that are still in development or testing before a stable release. They are denoted by appending a hyphen and a series of dot-separated identifiers to the version number, such as 1.0.0-alpha or 1.0.0-beta.1. These versions allow developers to release early versions for testing and feedback while clearly indicating their status.

Once we publicly release a version of our software, it is crucial to maintain consistency and avoid altering it retroactively. Any necessary fixes needs to be addressed through subsequent releases, typically indicated by an increment in the patch number. For instance, Python 2 reached its final version, 2.7.18, in 2020, more than a decade after the release of Python 3.0. If the developers decided to discontinue support for an older version, leaving vulnerabilities unresolved, they would have to transparently communicate this to their users and encourage them to upgrade.

Challenge 1: Semantic Versioning Decision Making

Imagine you are a developer working on a Python library called

DataTools, which provides various utilities for data

manipulation. The library uses semantic versioning and is currently at

version 1.2.3. You have implemented a new feature that adds support for

reading and writing CSV files with custom delimiters.

According to semantic versioning, should you bump the version to

1.3.0, 1.2.4, or 2.0.0? Explain

your reasoning.

Think about whether the new feature introduces any breaking changes for existing users.

According to semantic versioning, since the new feature adds

functionality in a backward-compatible manner, the version should be

bumped to 1.3.0. This signifies a minor version

increase.

Versioning vs Version Control

Note; although they share similarities, you should not confuse software versioning and version controlling your software. The table below outlines some similarities and differences to help you differentiate them:

| Aspect | Version Control | Versioning |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Tracking changes, enhancing collaboration, and maintaining a history of revisions | Differentiating between various stages of software development or releases, ensuring clear identification of updates and changes |

| Features | Branching, conflict resolution, merging | Version numbering, compatibility guidelines, and release notes |

| Example | Git | Semantic Versioning |

| Benefits | Collaboration, code integrity, and project management | Communication of changes (major, minor, patch), transparency, and compatibility |

| Challenges | Managing conflicts and merges with multiple contributors, ensuring training for teams, and integrating within existing processes | Ensuring backward compatibility and avoiding confusion with version numbers that accurately reflect the changes |

Dynamic Versioning using setuptools_scm

At this point, you might be thinking; “Do I have to manually

update the version number everywhere every release?”

Thankfully, the answer is no. Often, the version number associated to

your package will typically be in multiple locations within your

project, for example, in your .toml file and separately in

your documentation. This means that manually updating every location for

every release you have can be extremely cumbersome and prone to

human-error, and therefore, you should avoid manually updating your

versions. Fortunately, the setuptools library we looked at

in previous episodes can help us automate these tasks.

The most natural and simplest solution is to use setuptools_scm

(abbreviated as Setuptools Semantic Versioning), which is an extension

of the setuptools library. setuptools_scm

simplifies versioning by dynamically generating version numbers based on

your version control system (e.g. git). It can extract

Python package versions using git metadata instead of

having to manually declare them yourself.

There are 3 changes to your pyproject.toml file required

to get your project to build using the version number from the git tag

instead of the manual version value:

- Add setuptools-scm to the required packages

- Replace the manual version with a dynamic one

- Add the setuptools.scm table header to instruct the build process to use setuptools-scm

TOML

[build-system]

requires = ["setuptools"]

[project]

name = "fibonacci"

description = "A package to calculate the fibonacci sequence"

dependencies = ["pandas", "numpy"]

dynamic = ["version"]

[tool.setuptools_scm]Once you’ve set up setuptools_scm in your

pyproject.toml file, the workflow to version bump your

package will look like:

-

Commit your changes:

-

Add your changes and commit them in your Git repository.

-

-

Tag a new version:

-

Create a new Git tag to bump the version (e.g., from

v1.0.0tov1.1.0):

-

- Push the tag to your remote repo (e.g. GitHub):

-

Push the new tag to your remote Git repository if applicable:

-

Rebuild/reinstall your package:

-

When you build or install the package,

setuptools-scmwill automatically pick up the new version from the Git tag.Following this, you can confirm your new version by printing your package’s

__version__attribute. Ultimately, this means that your package’s Git tags,__version__,pyproject.tomland any other file containing your package version version will automatically updated and synchronised with each other. So when users or other developers are using your framework, they’re able to accurately tracking any code changes and dependencies, allowing them to reliably recreate specific versions of your software at any point in time.

-

Although setuptool_scm is the most common and simplest

tool for dynamic versioning, there are many alternatives that you may

consider in your own project. These include:

PDM - this is a Python package and dependency manager, which also supports the latest PEP standards.

Hatch - used for managing and publishing Python projects, and handling virtual environments and versioning. It’s also best suited for multi-environment and cross-version testing setups.

Rye - a lightweight Python project manager designed to simplify dependency management and virtual environments. This is generally ideal for users looking for a streamlined workflow.

Versioning is crucial for tracking the development, improvements, and bug fixes of a software package over time. It ensures that changes are documented and managed systematically, aiding in reproducibility and reliability of the software.

Tools like

setuptools_scmhelp automate the version bumping process, reducing manual errors and ensuring that version numbers are updated consistently across all project files.Versioning enables users to track code changes and dependencies, allowing reliable recreation of specific software versions, and further aiding the reproducibility of your software.